Time to Leverage the Strategic Potential of Andaman & Nicobar Islands

Summary: In recent years, India has adopted a proactive policy aimed at transforming the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a tri-services command, as an economic hub and one of the key centres of its defence and security strategy. A focused development plan for the Islands is expected to greatly enhance the country’s geopolitical leverage in the Indian Ocean Region. This policy brief recommends the opening up of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to the friendly navies of the US, Japan, Australia and France, among others, in order to promote greater naval cooperation.

Summary: In recent years, India has adopted a proactive policy aimed at transforming the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a tri-services command, as an economic hub and one of the key centres of its defence and security strategy. A focused development plan for the Islands is expected to greatly enhance the country’s geopolitical leverage in the Indian Ocean Region. This policy brief recommends the opening up of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands to the friendly navies of the US, Japan, Australia and France, among others, in order to promote greater naval cooperation.

In recent years, the Government of India (GOI) has adopted a proactive policy aimed at transforming the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (A&N Islands), a tri-services command, as an economic hub and one of the key centres of India’s defence and security strategy.

Until now, the balance between environmental preservation, tribal welfare, national security and economic development was skewed in favour of isolating the Islands due to strategic considerations. The economic potential of the A&N Islands had largely remained untapped. As the Islands provide India a commanding geostrategic presence in the Bay of Bengal and access to South and Southeast Asia, a focused development plan for the Islands is expected to greatly enhance the country’s geopolitical leverage in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).

The GOI constituted the Island Development Agency (IDA) on June 1, 2017 for the development of islands. For the first time, under the guidance of the IDA, an initiative has been taken for sustainable development in the identified Islands. Four islands of Andaman & Nicobar have been covered in the first phase. The focus is on creation of jobs through the promotion of tourism, seafood, coconut industry, etc. In the second phase, suitable sites in 12 more islands of Andaman & Nicobar have been covered.

The A&N Islands have played a key role in enhancing India’s regional engagement with the Bay of Bengal littorals.

This policy brief recommends the opening up of the A&N Islands to other navies such as the United States (US), Japan, Australia, and France, among others, in order to promote greater naval cooperation.

Strategic Context

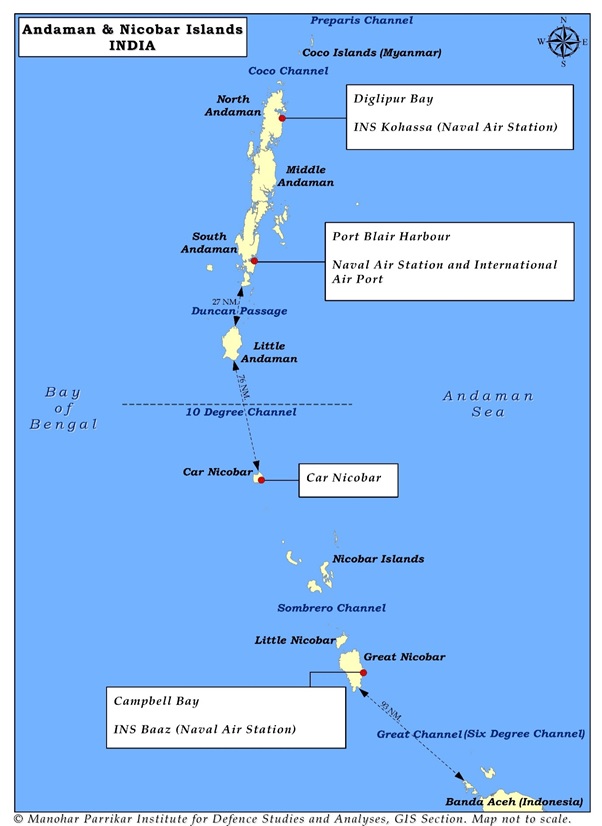

A combination of economic and strategic factors has significantly enhanced the strategic salience of the Bay of Bengal and its littorals. Strategically located, the A&N Islands, larger than several island countries in themselves, are an asset in India’s defence and strategic calculus. The Islands straddle Duncan’s Passage and the Ten Degree Channel. The Preparis Channel and Six Degree Channel are located to the north and south of the Island chain, respectively (see the map in Appendix A). All these passages are important trade routes for any shipping destined for Southeast and East Asia. The 572 islands, out of which only 38 are inhabited, comprise 30 per cent of India’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The Six Degree and Ten Degree Channels in the Andaman Sea which lead to the Malacca Strait are vital to the sea lines of communication (SLOCs) along which flows global commerce, including energy trade, between Asia, Africa and the Pacific. The A&N Islands are at the intersection of the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea, and further to the Pacific Ocean, an important fulcrum of the strategic concept of the Indo-Pacific.

China’s Forays in Indian Ocean

As China’s economic and strategic interests have grown in the Indian Ocean, so has its natural imperative to secure those interests. The fact is that the Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean is rather new and therefore quite logically seen as disruptive. Except for a brief period in the 15th century when Admiral Zheng He’s flotillas voyaged into the Indian Ocean, visiting Sri Lanka and southern India, China has never had an enduring historical presence in the Indian Ocean. This is different from the other great powers such as the US, France and Britain in particular, who have long maintained territory, populations and a naval presence in the Indian Ocean, going back an extended period of time. However, over the last decade or so, China has steadily expanded its maritime presence in the Indian Ocean littoral through a continuous deployment of its naval forces, arms sales, creating bases and access facilities, ramping up military diplomacy, cultivating special political relations with littorals, and lavishly disbursing developmental finance for strategic ends.

It has used the alibi of anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden to ramp up the scale and frequency of its presence, without consideration for the threat perceptions of India. An egregious example is the deployment of a submarine which berthed in Colombo in Sri Lanka in 2014, ostensibly on its way for so-called anti-piracy operations. China has also steadily enhanced its Operational Turnaround (OTR) in the Indian Ocean and developed new bases, including at Gwadar and Djibouti. This broad-based trend in the evolution of China’s presence is also reflected in the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal, where Chinese naval and survey vessels have been on the prowl and have occasionally entered India’s EEZ without prior intimation. China’s economic and strategic engagement with Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia in the Bay of Bengal/Eastern Indian Ocean has been noticeable in recent years.

Access to Andaman and Nicobar Command

The Tri-Services Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC) has progressively emerged as a lynchpin of India’s regional maritime engagement in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Various multilateral and bilateral maritime engagements viz. the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), the MILAN series of exercises, coordinated patrols, and bilateral exercises with littoral states in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea have contributed to this purpose. As regional maritime forces have expanded their cooperation with the Indian Navy in recent years, there is a new appreciation in Southeast Asia about India’s potential in offsetting China’s dominance of littoral-Asia.

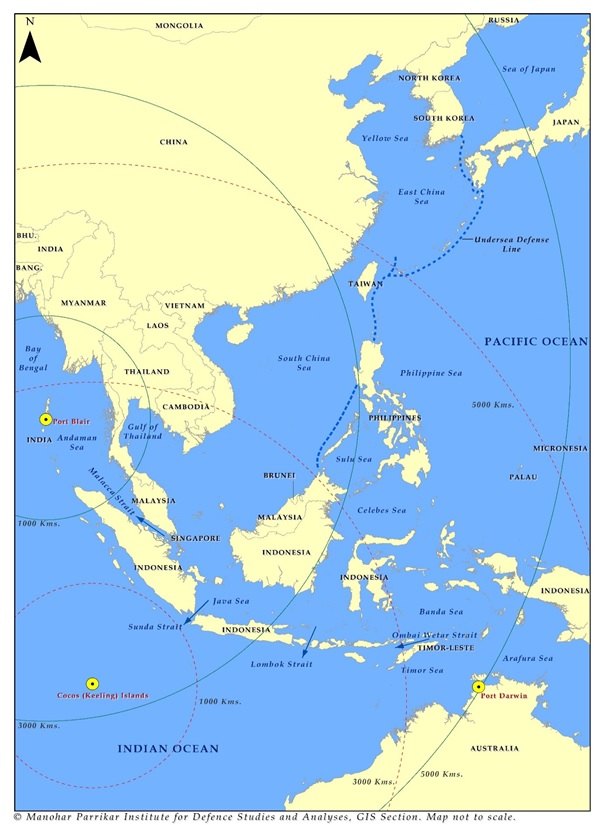

While regional navies of Southeast Asian countries have been making regular port calls to Port Blair, other major navies viz. the US, Australian, Japanese and French have shown interest in visiting the Andaman Islands for port calls and exercises. There have been some suggestions for coordinated surveillance of Malacca, Sunda, Lombok, and Ombai Wetar Straits through the collaborative use of the A&N Islands and Australia’s Keeling (Cocos) Islands. Similarly, there have also been some recommendations about collaborative anti-submarine warfare (ASW) efforts in the Indian Ocean in which the A&N Islands could play a critical role.

A few visits by other navies to the A&N Islands have taken place in recent years. The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) has been participating in the MILAN series of exercises from 2003 onwards, which take place in the A&N Islands. Also, the RAN warships have made a few visits to Port Blair. A Japanese flotilla of minesweepers had visited Port Blair in 2011. The French Naval Ship Var, a logistics support ship, had visited the A&N Islands in 2006. Similarly, a Royal Navy flotilla of the United Kingdom (UK) also visited the A&N Islands in 2003. It needs to be highlighted that these visits have not only been sporadic but have also been kept low-key with limited publicity, if any.

However, when it comes to the US, none of its naval ships or aircraft have been given access to the A&N Islands in the past. This is a matter which needs to be rectified in light of the fact that India and the US have a Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership and the US is today India’s biggest defence partner.

Institutional Reluctance

Notwithstanding episodic visits by other navies, there exists some traditional institutional reluctance towards allowing port visits to the A&N Islands by foreign navies in general and the US Navy in particular. The origins of such a stand may lie in the past when the geopolitical situation was completely different.

The broader arguments against opening the A&N Islands to other major navies could have been based on considerations such as:

(a) If naval vessels and military aircraft of other major navies become regular visitors to the A&N Islands it could accentuate China’s ‘Malacca Dilemma’. Given the complexity of India-China bilateral relations, these strategic interactions at the A&N Islands may rile China and lead to further antagonism between the two countries.

(b) Enhancing interaction through visits by warships and military aircraft could be a ‘slippery slope’ which could progressively lead to more complex demands for strategic collaboration through the joint deployment of naval and military assets for other contingencies beyond the scope of India’s direct strategic interests.

(c) India may be seen as part of a collaborative framework against China in which other countries are already in a declared military alliance, for example, US-Australia, US-Japan, etc.

(d) In case India takes a liberal approach towards visits by other major powers, there should be a substantive quid pro quo particularly in relation to the US and Australia.

Analysis of Considerations

The entire approach to the question of allowing the naval assets of other major powers – including friendly powers and partners – appears to be predicated on its conjectured impact on India-China dynamics. This appears to be the central reservation.

The China-centric approach to India’s decision-making appears flawed for the following reasons:

(a) India has complete sovereignty, territorial control and rights over its own territory. It is entirely for India to decide whether and which foreign navies can pay a visit to the A&N Islands. The Malacca Strait is an international waterway. Hundreds of nations ply their naval and merchant ships through those waters, including Japan, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and others. It is not used exclusively by China, nor does China have a lien on defining its strategic importance. Simply because it is a potential choke-point does not mean that there is any intention on the part of India or any foreign naval vessel that India permits to visit the A&N Islands, to threaten China’s trade and energy flows through that waterway. In any case, foreign navies are regularly traversing the Malacca Strait and the international waters off the A&N Islands.

(b) On its part, China does not show any concern for India’s sensitivities in its deployments in the Indian Ocean, not even when visiting its immediate vicinity. This is not analogous to foreign navies being permitted by India, on a case-by-case basis, to access the A&N Islands. Such action is not taking place in China’s immediate vicinity. India needs to delink visits by friendly navies to the A&N Islands from the so-called China factor (China’s “Malacca Dilemma”).

(c) Allowing foreign naval vessels to visit the A&N Islands on a case-by-case basis does not tantamount to a “slippery slope”. It is entirely up to India to assess any future requests by foreign navies and decide whether to accede to requests for a strategic collaboration – including proposals for joint exercises – on a case-by-case basis. India retains the right to decline any activity that goes beyond its strategic interests or areas of operation.

(d) Ship visits are a normal and natural part of naval cooperation between friendly nations. This has no bearing on whether the visiting naval power has a defence partnership or alliance with third countries. China has held joint exercises with Pakistan in the Indian Ocean, and recently with Iran and Russia in the Persian Gulf and also with South Africa and Russia in the western Indian Ocean. India’s concerns have not been a factor for China.

(e) If India allows the US Navy or any other navy to visit the A&N Islands, indeed, there should be a well-considered quid pro quo.

Imperatives for Review

An evaluation of the current policy must factor in China’s unilateral approach and growing strategic objectives in the Indian Ocean. India’s ‘strategic autonomy’ should help it take a decision which is independent of any speculative assessments of Chinese perceptions of India’s cooperation with other navies around the A&N Islands.

Notwithstanding the self-imposed restraint by India in regard to granting access to the A&N Islands, China has shown scant regard for India’s sensitivity in regional geopolitics. China’s naval presence and strategic engagements in the IOR have constantly seen accretion. Along with the permanent presence of a naval flotilla in the Gulf of Aden, Chinese submarines and research vessels are making regular forays in the IOR. Of particular note is China’s growing presence in the Bay of Bengal, and its strategic engagement with Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Thailand which has significantly enhanced in recent years. The violation of India’s EEZ around the A&N Islands by a Chinese research vessel in December 2019 had illustrated China’s growing strategic presence and intentions in the Bay of Bengal.

India’s strategic engagement of its partners through visits by their navies to the A&N Islands cannot be construed as an alliance framework. In recent years, India has concluded logistics-sharing agreements with the US and Australia, as well as with France, Singapore and South Korea. A similar logistics-sharing agreement with Japan is in an advance stage of negotiations. The progress on these foundational cooperative agreements, especially with the countries involved in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) or the QUAD Plus, like South Korea, indicates that these apprehensions have been overcome.

Need for Collaborative Strategic ASW

The access to the Indian Ocean from the Pacific Ocean and vice-versa is limited through defined chokepoints which include Malacca, Sunda, Lombok, and Ombai Wetar Straits. Surveillance around these chokepoints is necessary for monitoring the movement of foreign naval vessels, particularly Chinese warships and submarines. In so far as submarines are concerned, submerged transit through the Malacca Strait is prohibited by regulations and is nearly impossible given the traffic density. The Lombok and Ombai Wetar Straits, however, do provide scope for submerged transit.

Given China’s growing economic and strategic interests, Chinese naval presence in the IOR is expected to increase, including regular forays by Chinese nuclear submarines. While monitoring warships is relatively simpler, keeping track of Chinese submarines through a wide strategic anti-submarine warfare (ASW) network is an asset-intensive and complex task. A comprehensive maritime domain awareness (MDA) would require granular and accurate knowledge of both surface and sub-surface actors.

The US and Japan have a robust collaboration in strategic ASW in the Pacific through a combination of a sound surveillance sensor (SOSUS) chain and long-range maritime patrol (LRMP) aircraft. A similar approach for strategic ASW surveillance has been suggested in the Indian Ocean through collaboration between India, Japan, Australia, and the US. In addition, there are suggestions that India and Australia could consider a collaborative deployment of their LRMP aircraft from India’s Andaman Island and Australia’s Keeling (Cocos) Islands (ranges indicated on the map in Appendix B).

Recommendations

The A&N Islands are a strategic asset for India to assert its dominance on the major East-West maritime trade route that passes through the Malacca Strait. It has often been referred to as India’s ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ to the East. As close to 80 per cent of China’s seaborne trade passes through this region, the possibility of it being throttled raises the spectre of the ‘Malacca Dilemma’ for China. Yet, there is no reason to deny the US, Japan, Australia, France or the UK access to the A&N Islands. Port visits can lead to further graded cooperation in all its dimensions in the A&N Islands between India and its key strategic partners.

Geographically, India does not stand to gain in any substantial way by seeking a quid pro quo to operate from Diego Garcia, the US/UK base in the IOR. It can complicate India’s relations with Mauritius which has a historical claim over Diego Garcia/Chagos Archipelago (a claim supported by India in the International Court of Justice and the United Nations General Assembly). However, India can consider seeking in return advanced ‘military technological transfer’ and transfer of sophisticated weapons which the US may now, under the current geostrategic situation in the Indo-Pacific, be willing to provide to India.

Access to the US assets to carry out operational turnaround (OTR) at the A&N Islands is in accordance with the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA), which is a bilateral matter that brooks no third-party interference or consideration.

In so far as Australia is concerned, the two sides have recently upgraded their ties to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” at the virtual summit on June 4, between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Prime Minister Scott Morrison. Among the key pacts concluded were Mutual Logistics Support Arrangement and a Joint Declaration on a Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. In its 2017 White Paper on Foreign Policy, Australia recognised India as a “pre-eminent maritime power among Indian Ocean countries” and a “front-rank partner of Australia”.

The strategic relevance of reciprocal access to the A&N Islands and the Keeling (Cocos) Islands needs to be mutually appreciated along with the significance of Darwin, on the northern seaboard of Australia overlooking the Lombok and Sunda Straits. While there exists a robust MDA information-sharing agreement between India and Australia, the two sides should consider expanding the scope of cooperation by formalising a protocol for ensuring an effective underwater surveillance system. This may include technical collaboration for a SOSUS chain around Sunda and Ombai Wetar Straits. For this, both India and Australia should engage Indonesia as a key participant.

Appendix A

Geographical Details: The A&N Islands

Appendix B

Strategic Surveillance: A&N Islands and Keeling (Cocos) Islands

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.