Nexus of Drug Trafficking and Militancy Exposed at New Delhi

The link of drug trafficking and security was once again highlighted by the recovery of 200 kg of banned Ephedrine drugs worth Rs. 2 crore from Napoleon Thockchom, who was on his way to New Delhi’s international airport on April 2, 2011.

Napoleon Thockchom is suspected to be a member of the outlawed Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP, Military Council) Lalihba group of Manipur. The incident not only raised concerns about the security set-up at the New Delhi airport related to cargo intake, but also about other problems associated with drug trafficking that affects national security. It has exposed the narcotic operational network of the northeast insurgents who raise funds through drug trafficking for continuing their insurgency.

According to the Delhi Police, the consignment was concealed in 20 courier cardboard boxes containing packets, each with 500 grams of the drug. It has raised serious questions regarding the security arrangement of the various courier services operating in the civil aviation sector. Technically, every commodity meant for flight cargos is scanned through computerized X-ray machines installed at the cargo stations. The possibility of a consignment being sneaked in through the cargo service with the knowledge of the security in-charge of the service provider cannot be ruled out. This shows the possibility of a nexus between cargo service providers and traffickers, which requires a re-evaluation of the security arrangement of services related to aviation. The incident cannot be taken lightly considering the deteriorating security environment of the country marked by frequent terrorist attacks in recent years and the threat of the same in future.

According to reports of the Narcotic Control Bureau of India, India produces approximately 500 tonnes of Ephedrine annually for the pharmaceutical industry. The major production units are concentrated in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. In Asia, India and China are the main manufacturers of Ephedrine, which is used for extracting ATS (Amphetamine-Type Stimulants), a synthetic drug that is replacing heroin, opium and cannabis.1 Most of the ATS trafficked around the world is destined for Cambodia, Canada, Spain, Taiwan, the Philippines and the United Kingdom, where the demand is high. Between 2004 and 2010, Indian law enforcement agencies have made significant seizures of Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine. But the illicit siphoning off of legitimate drugs, in spite of the strict control measures put in place by the Government of India, continues unabated.

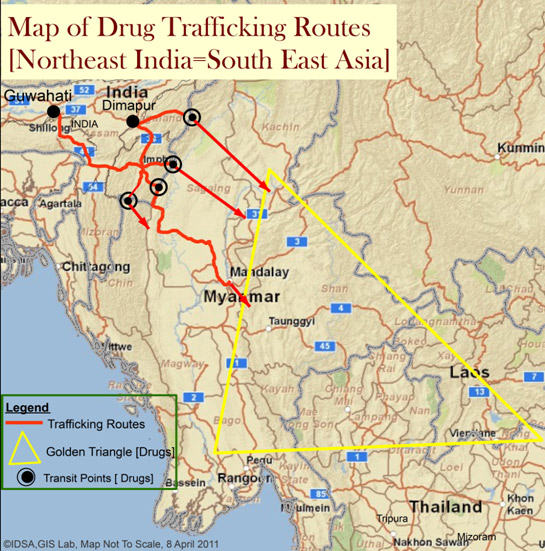

The emerging trend of Ephedrine trafficking is also related to its increasing demand by the illicit ATS industry in Myanmar. ATS smuggling is posing a serious challenge to the law enforcement authorities trying to curb the manufacture and trafficking of synthetic drugs. On June 30, 2010, an Indo-Myanmar basic contact field level officers’ meeting on drug control was held at Moreh by the Anti Narcotics (Special) Task Force, Tamu, Myanmar, to curb smuggling of drugs on both sides of the international border. But the initiative was futile, as most parts of the border remain porous. Drugs like Ephedrine are covertly taken through diverse routes up to the Indo-Myanmar border in the northeast, with the help of armed militant groups operating along the border. Once the consignments are handed across the border, they are transported by Tamil expatriates, mostly of Indian origin, living along the Indo-Myanmarese border and who are well-connected with drug dealers inside Myanmar.

In the northeast of India, particularly in Manipur, militancy has been associated with drug trafficking since the 1990s. The seriousness of trafficking was first highlighted in 1992, when ethnic conflict broke out between the armed militant groups of Nagas (NSCN) and Kuki (KNA) tribes, which wished to dominate drug trafficking and smuggling in Moreh, a border town in Chandel district. Being located close to the infamous Golden Triangle, most of the drugs intrude inside northeast India from Myanmar. The Indo-Myanmarese border in the Manipur sector has more than ten routes (un-mantled roads) located in Ukhrul, Thoubal, Chandel and Churachandpur districts. In the last decade, after the Myanmar and the Thai governments cracked down on the opium production hubs along the Myanmar-Laos-Thailand borders, the drug peddlers have switched over to production of synthetic drugs like ATS, methaqualone or mandrax, methamphetamine, Ketamine, opirates, etc.2

Traditionally, cross-border trafficking of drugs from northeast India was rare and the Manipur Valley-based insurgent groups did not indulge in drug related activities. But this changed subsequently. With enhanced deployment of security forces along the Indo-Myanmar border and successful counter-insurgency operations like “Operation All Clear” which had deprived them of their bases in the remote hill areas, the militants received a setback. They are looking for new hideouts, trying to regroup and set a positive image by not indulging in extortions from the masses. This has been the reason for the militant groups such as KCP and KYKL (Kanglei Yawol Kanna Lup) to adopt drug trafficking to fund their organisation and activites. Moreover, the image and the organisational structure of the militants have become weak in recent years, especially given the loss of vital support from the masses. Numerous groups have arisen out of a single group and many are operating with sophisticated small arms in nexus with the drug mafias.

Militants have become involved in the drug trade, which generates billions of dollars in the black market, approximately 300 times the capital investment. It has become a major source of funding for the militant organisations to procure sophisticated arms. Drug trafficking thus contributes for the continuance of militancy in the northeast, despite the range of counter-insurgency operations and developmental activities. Therefore, it is impossible to resolve militancy in northeast India without tackling the menace of drug trafficking.