Military Logistics Agreements: Wind in the Sails for Indian Navy

India has signed four military logistics support agreements with partner countries and is in the process of finalising the fifth with Russia. The issue came up for discussion during the recent visit of Defence Minister Rajnath Singh to Russia from November 05-07, 2019.1 When signed, the agreement with Russia, termed the Reciprocal Logistics Support Agreement (RLSA), will be an important milestone in bilateral relations. As the name signifies, the Agreement will facilitate reciprocal usage of logistics facilities by the militaries of both nations during visits to each other’s ports, bases and military installations.

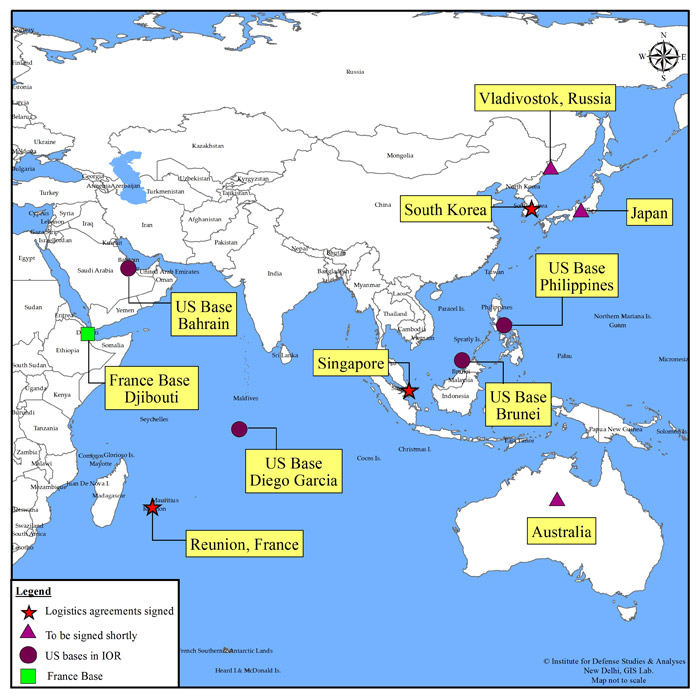

This Agreement is similar to the four other logistics agreements India has signed with partner countries, viz., Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) with the United States (US) in August 2016, Implementing Arrangement Concerning Mutual Coordination, Logistics and Services Support with Singapore in June 2018, Agreement for the Provision of Reciprocal Logistics Support between the Armed Forces with France in March 2018, and, most recently, Agreement to Extend Logistical Support to each other’s navies with the Republic of Korea (ROK) in September 2019. Similar agreements are in the pipeline to be signed with Japan, United Kingdom and Australia.

Logistics agreements are administrative arrangements which help to facilitate the replenishment of fuel, rations, spares (where required), and berthing and maintenance for the other nations’ warships, military aircraft and troops during routine port calls, joint exercises and training carried out in each other’s countries as well as during humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR). These agreements simplify the bookkeeping during such events and ensure that the forces of the visiting countries are benefitted by using the host nation’s existing logistics network, which additionally reduces overall costs and saves on time.

These agreements feed into the Indian Navy’s requirement to maintain round-the-clock and round-the-year presence in its primary areas of interest, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) and, going forward, the Indo-Pacific. The Indian Navy has been maintaining presence through its concept of mission-based deployments, wherein over a dozen major surface combatants are deployed across the length and breadth of the IOR. These deployments have contributed, among other things, to significantly enhance India’s maritime domain awareness (MDA) picture, facilitate tracking of vessels of interest and also to be the first responder in case of a developing HADR scenario.

Prior to these agreements, the mission-deployed Indian warships were constrained to periodically replenish their fuel and logistics supplies from either an Indian naval fleet tanker deployed in the area or by entering the nearest Indian or foreign port. With the signing of these agreements, Indian warships have been able to extend their ‘sea-legs’ on station by taking fuel from naval fleet tankers of partner countries deployed in the region or by entering their ports.

For instance, since the signing of LEMOA with the US in 2016, Indian warships deployed near the Gulf of Aden have been fuelling from the US Navy tankers in the region and similarly have the flexibility to fuel from the US naval tankers worldwide or enter ports under their control when required. The versatility and reach of this arrangement was highlighted recently when INS Kiltan, an Indian Navy anti-submarine warfare corvette, conducted replenishment-at-sea (RAS) with US Merchant Marine vessel USNS Richard E. Byrd, a Clark–class dry cargo and ammunition ship, in the South China Sea.2 Also, having signed the logistics agreement with France in 2018, Indian warships and military aircraft can utilise the French base of Djibouti in the Horn of Africa or the French territory of Reunion Islands in the Indian Ocean for a quick ‘turn-around’ of its assets.3 A logistics agreement with Russia would give the Indian Navy access to the Arctic seaports, which are likely to be ice-free for longer periods in the future due to global warming.

In addition to extending the range of Indian warships, such agreements provide for added operational flexibility of the Indian Navy’s long-range maritime patrol (LRMP) aircraft. The Indian Navy has in its inventory the extremely potent Boeing P8I acquired in 2013. The aircraft carries a variety of state-of-the-art weapons and sensors that are capable of engaging both surface and subsurface targets. With an operational range of 1200 nm (with four hours on station) and speed of 789 kmph, the aircraft forms India’s maritime ‘first line of defence’.4 The logistics agreements with partner countries thus facilitate the landing and refuelling of these aircraft at reciprocal bases, as agreed, thereby extending their operational envelope by a substantial degree.

The logistics agreements in certain ways also divests the need for a nation to invest in overseas bases or dual-use infrastructure. This is because the efficacy of overseas bases would have to be measured vis-à-vis installation, maintenance and manpower costs. Therefore, depending on a nation’s strategic interests in a region, the development of overseas bases has to be assessed against the relative flexibility that a logistics agreement provides for expanding a nation’s operational footprint and diversifying its international presence at the same time at a much lesser cost.

Signing of these agreements has been in consonance with India’s growing maritime engagement with navies of the Indo-Pacific. The Indian Navy presently carries out bilateral naval exercises with fourteen navies and coordinated patrols with four, most of which are in the Indo-Pacific. The recent India-Singapore-Thailand Joint Maritime Exercise, conducted at Port Blair on September 16, 2019, has further added to the Indian Navy’s repertoire of joint exercises conducted in the region.5 Such operational engagements, coupled with the signing of logistics agreements, indicate maturing of strategic trust between nations.

The timing of India’s aforementioned logistics agreements with respect to the then prevalent geostrategic calculus is also interesting. US President Barack Obama had announced his ‘Rebalance to Asia’ strategy in 2011. In September-October 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping had proposed the ambitious ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ and ‘21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ or ‘One Belt, One Road’, later renamed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was preceded by more than a decade of aggressive maritime infrastructure development by China in most of the IOR littoral countries surrounding India. This included the development of islands in the South China Sea, constant forays of Chinese warships into the Indian Ocean and acquisition of a military base at Djibouti. China’s increasing economic and military heft thus required an effective counterbalance. As can be inferred, all the four logistics agreements India signed were after 2016, the first being LEMOA with the US.

India has managed to steer a straight course through the choppy geostrategic environment by concluding military logistics agreements with the US, France, Singapore and South Korea, and is looking forward to signing a similar agreement with Russia shortly and more to follow. The endeavour has been to increase cooperation in the field of maritime security, joint exercise, HADR and interoperability between navies. Though Indian warships can always extend their operational reach by using their fleet tankers, the availability of logistics support facilities with other countries will further enhance the ability of the Indian Navy to maintain appropriate ‘presence’ for extended periods in its areas of interest in the wider Indo-Pacific.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Raksha Mantri Shri Rajnath Singh co-chairs IRIGC-M&MTC meeting with his Russian counterpart General Sergei Shoigu,” Press Information Bureau, Government of India, November 06, 2019 (Accessed November 08, 2019)

- 2. Ankit Panda, “US Merchant Marine Ship Replenishes Indian Navy Ship in South China Sea,” The Diplomat, November 06, 2019 (Accessed November 08, 2019)

- 3. “Indian Navy benefits from strategic logistics pacts with US, France,” The Economic Times, June 16, 2019 (Accessed November 04, 2019)

- 4. “P-8I Aircraft: 21st Century Maritime Security for the Indian Navy,” Boeing, January 2014 (Accessed November 05, 2019)

- 5. “Sea Phase of maiden IN-RSN-RTN Trilateral Exercise Commences,” Press Information Bureau, Government of India, September 19, 2019 (Accessed November 05, 2019)