Contest and Cooperation in the Arctic

At the 2010 Arctic Summit hosted in Moscow, the key question – albeit couched in terms of environmental and cultural preservation and development – has been one of shared exploitation of the region’s natural riches. Home to 22 per cent of the world’s “untapped but technically recoverable hydrocarbons,”1 the Arctic has witnessed a number of controversial developments in recent memory.

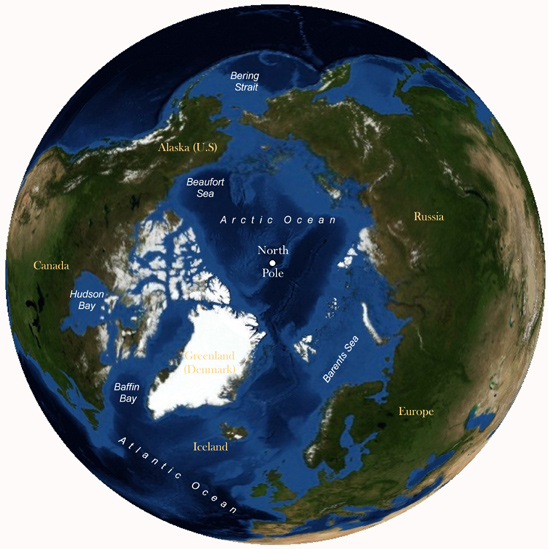

Despite pre-existing unilateral Russian and Canadian claims dating from the 1920s, the Arctic Ocean was treated as International Waters for the best part of the last century. But with shrinkage of polar ice-caps through the effect of climate change, the North Pole and along with an estimated quarter of the world’s oil and gas reserves are within easier grasp than ever before. In addition to determining sovereign rights over mineral exploitation, at stake are also other resources such as sedentary organisms (crabs, clamps and corals) located on the sea-bed and sub-sea floor.

Through the course of the first decade of this century, all proximate parties – Canada, the US, Norway, Denmark and Russia – have made official submissions claiming parts of the contested Lomonosov Ridge as rightfully belonging to their respective sovereign jurisdictions. In 2001, Russia claimed the Lomonosov Ridge as part of its own extended continental shelf. Simultaneously, Canada has been assertive of its claims over the Lomonosov Ridge and alongside flexing its military muscle in the region has also declared its intent to defend these claims at the level of the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Another party to have submitted counter-claims and conducted expeditionary work is Denmark through its union with Greenland. Up for grabs, in the last analysis, is an exclusive economic zone spanning 1800 kms, including the North Pole and resource-rich sites such as the Stockman and Snohvit fields.

In mid-September Russia and Norway came to an agreement on a matter that had been deadlocked since the 1970s, delimiting their respective maritime boundaries in the Barents Sea and Arctic Ocean. Scientific communities of the United States and Canada have similarly been co-operating towards gathering evidence that will eventually help establish sovereign rights over their overlapping extended continental shelf in the region, tellingly referred to as “ice-breaker work”, given latent and explicit hostilities that have shrouded this dispute. Overall, the parties seem in agreement that a rule based system towards governance of the belt is called for and that such a system must be derived from pre-existing rules governing the high-seas.

The most relevant provision in International Law to inform this process has been identified as Article 76 of the Convention on the Law of the Sea. Under the provisions of this article, “each nation has a ‘continental shelf’ that extends to the outer edge of its continental margin or to a distance of 200 nautical miles (nm) from its coastal baselines if the continental margin does not extend that far.”2 The Ilulissat Declaration of 2008 firmly rejected the possibility of resolution by a separate International Treaty, pronouncing the Law of the Sea as the adequate and appropriate legal framework. Against a backdrop of actor proliferation, this stance has been reaffirmed by Russian leaders.

Underground explosions are being conducted to determine the rock-type of the Ridge in a bid to find matches with respective continental shelves. Harshness of terrain and climatic conditions allow scientists to engage in experimental work for only a few weeks a year, tipping this to be a long drawn process. As has most recently been the case with evidence on climate change, the contested nature of scientific fact-finding and the conclusions it yields are likely to thwart co-operative action.

Despite considerable progress in demarcation of sovereign jurisdictions, oceans today continue to be an arena for clash of interests and consequent conflicts and in years to come the global gaze will be steadily trained on the Arctic to follow developments there. Whereas international organisations such as the UN and NATO have already been involved, actors like Sweden, Finland and energy-hungry emerging economies will no doubt seek a role for themselves moving forward. With its icebreaker Zuelong, China’s own scientific expedition is already underway.3

Environmental watchdogs also warn of possible hazards associated with exploration in the region.4 Moving icebergs could rupture oil and gas pipelines causing spills with potentially disastrous consequences for biodiversity and ecological health. Through its working groups on monitoring climate change, pollution prevention and biodiversity conservation, the Arctic Council,5 one hopes, has the wherewithal to deal with these challenges.

Whether the lack of a comprehensive Arctic treaty will result in a scramble by oil companies and regional naval powers remains an outstanding concern. Diversity of actors, interests and institutions and the slow pace of exploration owing to geographic and financial constraints should together avert escalation into Borgerson’s “Hobbesian free-for-all” scenario6 at the very least.

- 1. N. Otens, “Rise, Arctic, Rise!,” Arctic Sentinel, September 23, 2010.

- 2. Website of the US Extended Continental Shelf Project, http://continentalshelf.gov/missions/10arctic/background/shelf.html

- 3. “Norway Welcomes China to the Arctic,” BarentsObserver.com, August 31, 2010.

- 4. “WWF: Shtokman project must be stopped,” BarentsObserver.com, September 13, 2010.

- 5. Established by the Ottawa Declaration of 1996, the Arctic Council is a member organization comprised of Canada, Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russian Federation, Sweden, and the United States of America, with a rotating Presidency.

- 6. S. G. Borgerson, “The Great Game Moves North,” Foreign Affairs Website (Postscript: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/64905/scott-g-borgerson/the-great…), March 25, 2009.