Why Bodo Violence Continues to Recur?

The Bodo areas in Assam are witnessing bloodshed once again. The National Democratic Front of Bodoland (Songbijit faction) [NDFB-S] is alleged to have targeted the Adivasi settlers in the two districts of Sonitpur and Kokrajhar, killing nearly 78 and leaving many seriously injured. It appears that this carnage started in retaliation to the death of three NDFB (S) cadres during a counter-insurgency operation conducted by the Mahar Regiment on December 21 against the outfit’s camp in the Chirang District along the Assam-Bhutan border. Information from the ground reveal that the NDFB-S may have targeted the Adivasi settlers near the forest areas suspecting them of providing intelligence about their movement to the counter-insurgency forces.

The faction is known to have regularly targeted people both from Bodo and non-Bodo ethnicities on suspicion of being police informants, like the case of a 16-year old Bodo school girl who was dragged out of her house, beaten and then shot to death by the NDFB militants in Dwimugri village on the Indo-Bhutan border in August 2014. The causes for recurring violence in the Bodo areas are deep-rooted. The Adivasi settlers are viewed by the Bodos as slowly establishing a large presence in the state along with other migrants, thus relegating Bodos to minority status.

Violent Background

A similar situation had occurred in May 2014 during the Lok Sabha elections when 41 bodies were discovered in Baska and Kokrajhar districts. At that time too, the NDFB-S was suspected to be behind the violence. The non-Bodos, including migrant Muslims, who constitute the majority, alleged that their failure to vote for the Bodo People’s Front (BPF) candidate, Chandan Brahma, resulted in the fatal retaliation. This was linked to the remarks by a BPF leader, Pramila Rani Brahma, who had commented on April 30 that the Muslim migrants had not voted for Chandan Brahma. Instead, Muslims had propped up their own independent candidate, Naba Kumar Sarania alias Hira Sarania, a former United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) rebel from Kokrajhar. This seat which had always been represented by a Bodo parliamentarian saw the victory of the first non-Bodo: Sarania.

To dwell further back, it was in 1993 when the first large-scale massacre had occurred in which 50 migrants were killed in Kokrajhar and Bongaigaon districts. In 1994, 100 migrants were similarly killed in the Bodo areas. In 1996, another minority community, the Santhals, was targeted by the Bodos leading to the death of 200 people and displacement of thousands. In 2008, very similar to the latest round of violence, about 100 people were killed and nearly 200,000 displaced in clashes between the Bodos and the minority communities. In 2012, again nearly 96 people had lost their lives and 400,000 were displaced in another such violent incident.

Deciphering Causes

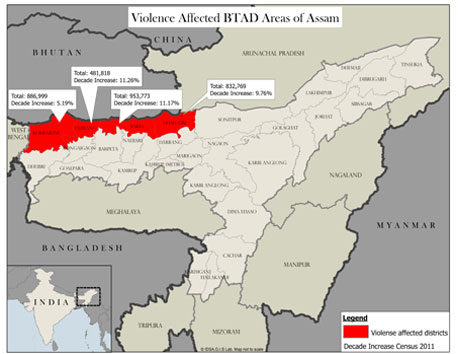

Though the underlying causes of the recurring violence are complex, they can be deciphered. First, the political empowerment of the minority communities in the Bodo Territorial Area District (BTAD) in recent years has resulted in growing unease in the Bodo community. The fear is about non-Bodo communities dominating the political process as seen in the election of Sarania. Second, political tension in the area is further compounded by the perception among the Bodos that illegal migration from Bangladesh is relegating them to a minority status in their own land. The Bodos at present constitute 29 per cent of the population, followed by the Rajbonshis (15 per cent), Bengali immigrants (12 to 13 per cent) and Santhals (6 per cent). Third, the ‘perception’ of massive illegal migration has generated a fear psychosis in the Bodo community that their ancestral lands will be illegally taken away by the migrants. The lack of any reliable data on the number of people migrating from Bangladesh into Assam further aggravates the situation. Fourth, the inclusion of illegal migrants in the voters list is viewed as a deliberate ploy to empower an outside group vis-à-vis the Bodos, so that the latter lose their distinct indigenous identity. This has created a siege mentality among Bodos.

The situation has been further compounded by the failure of the Bodo Territorial Council (BTC) to mitigate the fears of the Bodos. For instance, the Bodo Accord of 2003 clearly stated that the BTC will “fulfill the economic, educational, and linguistic aspirations and the preservation of land-rights socio-cultural and ethnic identity of the Bodos.” Despite these provisions the Bodos continue to feel insecure vis-à-vis the minority communities due to weak administrative institutions that have failed to lock in their rights. The divisive politics of the members of the BTC have also added to the insecurity. For example, in May 2012, the BTC Chief Hagrama Mohilary had accused the minority representative in the BTC, Kalilur Rehman of the Congress, of instigating the minority community against the Bodos, which had led to the death of nearly 96 people (both Bodo and non-Bodo), without offering concrete evidence to back up his claims.

The BTC has failed to assuage the fears of the non-Bodos too. In terms of composition, the BTC has 46 seats of which 30 are reserved for Scheduled Tribes (read Bodos), five for non-tribals, five are open to all communities and the remaining six are to be nominated by the governor of Assam from among the communities. In a Council, where policy decisions in terms of development packages, land revenue, business tax and so on are based on a majority vote, it is clear that the Bodos are the privileged lot. The BTC is also vested with powers under the Panchayati Raj system. While the Bodo Accord explicitly states that the non-tribal population will not be disadvantaged by the provisions of the Accord, in reality, their rights are not duly acknowledged by the BTC, creating enormous apprehensions. The final cause of the recurring violence is the existence of armed groups like the NDFB-S, the Birsa Commando Force (BCF) representing the Santhals, etc., which have the capability to challenge the authority of the state administration.

Of serious concern is the inability of the local law enforcement agencies to stop retaliatory violence in time. Be it the July 2012 or May 2014 incident or even the latest round of violence, there were intelligence inputs suggesting a possible strike by the NDFB-S in some of the villages. But the state machinery failed to take effective security measures in villages near the Assam-Bhutan border where the NDFB (S) has a presence. It is important to demonstrate security presence in areas where an armed outfit is expected to strike.

Groups like the NDFB (S) are propelled by a strategy of instilling fear through intimidation of the local people (especially non-Bodos) in areas where they operate. Their presence is vindicated by the local discourses that propagate how non-Bodos are coming in droves and settling down in Bodo areas, thereby illegally taking away the ancestral lands and properties of the original inhabitants. The absence of well-documented land records further perpetuates the sense of fear, which is not all together misplaced. In an atmosphere that is already highly polarised along ethnic lines, the local politicians too try to politicise and exploit the prevalent insecurities to serve their vested interests.

Policy Intervention

The way out of this violence is to concentrate on three important policy interventions. First, establish a land record system that is computerised and accessible to the local people, and which can address the fear of loss of land to the outsiders. Second, improve the presence of both the state civil administration and the law enforcement agencies in areas that are identified as highly susceptible to ethnic violence. Last, but not the least, the state and union governments need to work together to collate credible data on the flow of migrants into areas that have been included in the BTAD. This is also relevant for other areas like the hills of Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya and Nagaland, where despite provisions for safeguarding the ancestral lands, local people have the same anxieties and concerns, which could spiral into violence in the near future on a similar pattern.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India