US-Iran Hostilities in Times of Pandemic

Both Iran and the United States (US) are among the countries worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, even as they fight their respective battles against the virus, the hostilities between the two continue. Both countries allege each other of violating international law. The tensions between the two countries took a sharp turn last year when, for the first time since the Iran-Iraq war, a series of events resulted in significant deterioration of peace and stability in the Gulf region. It all began after the waiver provided by Washington on purchase of Iranian oil expired in May last year. However, the most recent escalation in the US-Iran tensions at a time when the world is reeling under the COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns in the region.

Continued Hostilities

On April 15, the American ships deployed in the Persian Gulf reported an “unsafe and unprofessional” conduct by 11 Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy (IRGCN) vessels.1 In response, American President Donald Trump ordered the United States (US) Navy to “shoot down and destroy any and all Iranian gunboats if they harass our [US] ships.”2 Later, on the eve of IRGC’s launch of its first military satellite – Noor 1 – IRGC commander Salami affirmed, “[that] any [US] move will be responded decisively, effectively and rapidly.” He added that “IRGC is serious in defending the national security, and sea borders, and marine interests of Iran.”3

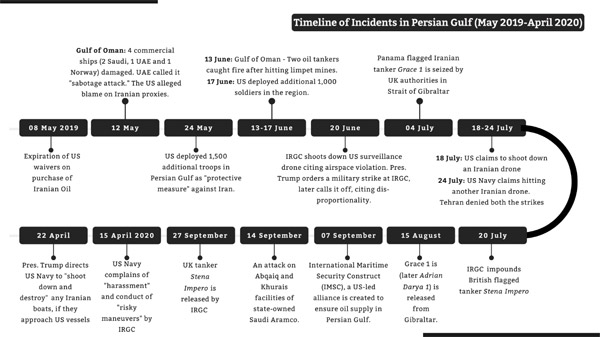

The recent confrontation between the two countries, which reached unprecedented levels after the killing of IRGC commander Qassem Soleimani in early January 2020, has once again raised concerns about stability in the Persian Gulf. In May 2019, after the expiration of the US waivers on the purchase of Iranian oil, several American tankers were attacked in the Gulf of Oman for which Washington blamed Tehran and its proxies.4 Iran forthrightly denied these allegations. Later, in June 2019, the tensions further escalated as the IRGC shot down a US drone in the Gulf. Consequently, President Trump ordered a military strike on Iran, which was later called off, citing disproportionality.5 As both sides decided to de-escalate, the situation at the time was brought under control with no significant harm.

Source: Compiled by the author from various media reports.

Though the recent skirmishes have again revived fears of a renewed escalation in tensions between the two countries, however, based on outcomes of the past incidents, one can discern a de-escalation pattern aimed at avoiding a full-blown war. In May 2019, when things began to spiral, both sides came out with statements repudiating the possibility of war. From the Iranian side, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei insisted that “There won’t be any war.”6 Similarly, the US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo ascertained that Washington “fundamentally” did not seek war with Iran.7

There seems to be an unsaid predisposition to manage the escalation plateau. A full-scale war in the Gulf would have long-term disastrous consequences for all parties involved – US, Iran and regional powers – and not to mention, the frightful impact it will have on the global oil supply. Similarly, when an attack took place on Saudi Aramco facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais in September 2019, the escalation was steadily followed by a de-escalation. Last year, both countries also presented their multi-state initiatives to manage escalations. The US-led maritime coalition in the Persian Gulf, known as the International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC), became operational on September 7, 2019.8 Two weeks later, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani announced a ‘Coalition for Hope’ or Hormuz Peace Endeavour (HOPE) at the 74th session of the United Nations General Assembly.9 However, the acceptability of these initiatives remains low, given the scepticism and deep mistrust in the region.

The recent tensions in April could be just another episode in brinkmanship between the two countries. It should be noted that the Iranian Navy’s actions came just a week before IRGC celebrated its 41st foundational day. Thus, the Iranian actions were more of posturing than any attempt at escalation. However, one cannot discount it entirely as semantics. From the IRGC’s perspective, it is believed that there is still a need to reinforce deterrence against the US after Soleimani’s death. In Washington’s viewpoint, it already has deterred Iran from taking bold steps by targeting its top commander in early January this year.

Yet, in the case of the Persian Gulf, sustaining deterrence is extremely difficult for two reasons. First, the deterrence, such as the one created by the US with the killing of Soleimani, is bound to diminish after some time. Second, the deterrence created on land (in Iraq or Syria) is entirely different from deterrence in the Persian Gulf. In Iraq, for instance, the US stakes are not as high as in the Persian Gulf enabling it to pursue risky policy moves. The Persian Gulf, on the other hand, is perceived by the US and Iran as a safe space, where it is relatively easier to project power with minimal risk of any large-scale retribution.

Prognosis

In the above context, it is important to identify potential developments that are most likely to guide the Washington-Tehran rivalry in the region. First, the arms embargo on Iran will be expiring on October 18, 2020. Already, Washington has started pushing for the extension of an arms embargo, but legal technicalities – due to the US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – makes it difficult for the US to achieve this easily. Meanwhile, the US Secretary of State Pompeo has made it clear that the US is “not going to let that [lifting of embargo] happen.”10 Washington’s influence at the UN is well-known, which the US is going to leverage to snap back the embargo.

Iran, on the other hand, has been preparing for the lifting of the embargo. In the last two years, it has moved to strengthen its partnership with both Moscow and Beijing that may help Tehran’s cause in October. Last year, in December 2019, Iran conducted a trilateral naval exercise in the Gulf of Oman with Russia and China to further enhance cooperation. Major General Mohammad Hossein Bagheri, Chief of Staff of Iranian General Armed Forces, has made multiple visits to Beijing and Moscow in the last couple of years. Earlier, in November 2016, Tehran signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement with Beijing followed by a military agreement in November.11 Moreover, both have also agreed to set up a joint technical and industrial commission.12 Similarly, Iran’s existing cooperation in Syria puts it in favourable conditions with Moscow. In mid-2015, Tehran had also acquired the S-300 Air Defence System from Moscow.

Furthermore, IRGCN’s ambitions also need to be factored in. The IRGCN, which so far has relied on small vessels to attain its objectives, has expressed its interest in developing a submarine fleet. The IRGCN commander made it apparent in the immediate aftermath of the confrontation with the US Navy on April 15.13 Whether enhanced capabilities will bring about any change in the way Washington views Tehran is something that remains to be seen. Tehran also has high hopes for the lifting of the embargo for which it has toiled hard to develop its partnership with two major powers. However, this partnership is unlikely to be of much assistance to Iran, except in the economic domain. Despite the COVID-19 crisis, Washington is likely to continue with the sanctions under its ‘maximum pressure policy’, something that Iran may find hard to manage given the circumstances.

To conclude, two factors are most likely to impact the current dynamics in US-Iran relations in the coming times. First, the probable consequences of the arms embargo on Iran that is scheduled to expire in October 2020. The ensuing push-and-pull will drive the rivalry further where Iran will attempt to hedge its bets with Russia and China. Furthermore, the uncertainty brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic would at best have a limited and short-term impact on the US-Iran hostilities. This is not to suggest that it would ease the rivalry, but the chances of escalation would remain limited, for the time being.

The author is thankful to Dr. Meena Singh Roy, Coordinator, West Asia Centre, MP-IDSA for her insightful suggestions and comments.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “IRGCN Vessels Conduct Unsafe, Unprofessional Interaction with US Naval Forces in Arabian Gulf”, US Central Command, April 15, 2020 (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 2. Donald J. Trump, President of the United States of America, Twitter Post, April 22, 2020, 5:38 PM (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 3. “Iran’s first military satellite put on orbit”, Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), April 22, 2020 (Accessed May 03, 2020); and “Cmdr: IRGC serious in defending Iran’s national sovereignty, security”, IRNA, April 23, 2020 (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 4. Interestingly, these attacks on tankers were seen by some as reminiscent of the Tanker War of the 1980s in the Gulf, during which 55 of the 239 petroleum tankers (23 per cent) from various countries were destroyed. This had led to a 25 per cent drop in commercial shipping and a rapid spike in crude oil prices. See “Are we seeing a repeat of the ‘Tanker Wars’ of the 80s in the Gulf?”, TRT World, June 13, 2019 (Accessed May 03, 2020); and “Tanker War”, Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law, August 2008 (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 5. President Trump revealed in his statement that the proposed attack would have resulted in around 150 deaths, which he claimed was a disproportionate response to the shooting down of an unmanned drone. See Donald J. Trump, President of the United States of America, Twitter Post, June 21, 2019, 6:33 PM (Accessed May 22, 2020).

- 6. “Iran’s Supreme Leader says there will be no war with US”, Reuters, May 14, 2019 (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 7. “US does not seek war with Iran, says Mike Pompeo”, BBC News, May 14, 2019 (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 8. The rise of tensions in the Gulf prompted Washington to stitch a coalition, formally known as the International Maritime Security Construct (IMSC), to provide safe passage to ships sailing through the Persian Gulf. The coalition has opened a command centre in Bahrain, which also houses the US Fifth Fleet. See “Maritime coalition launched to protect Gulf shipping after Iran attacks”, Arab News, November 07, 2019 (Accessed May 20, 2020).

- 9. Introduced by Iran, this initiative seeks to promote peace, stability and prosperity in the region by maintaining freedom of navigation and energy security for all. The initiative is based on the principles of international law, such as good neighbourliness, respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity, and peaceful resolution of disputes, non-aggression and non-intervention, among others. See “President at the 74th Session of the UN General Assembly”, Official Website of the President of the Islamic Republic of Iran, September 25, 2019 (Accessed May 21, 2020); and “FM Zarif’s Al-Rai Article on Hormuz Peace Endeavour”, Iran Watch, October 10, 2019 (Accessed May 20, 2020).

- 10. “Secretary Michael R. Pompeo At a Press Availability,” U.S. Department of State, April 29, 2020 (Accessed May 20, 2020).

- 11. Not many details have been made public, but the partnership is intended to increase cooperation between the two militaries by promoting defence diplomacy. This move is likely to benefit Iran by providing it access to various latest technologies related to defence research and information technology.

- 12. “We will witness significant development in Tehran-Beijing relations: Iran military chief”, Mehr News Agency, September 12, 2019 (Accessed May 03, 2020).

- 13. “Developing nuclear submarine on agenda of Iran’s Navy: cmdr.”, Mehr News Agency, April 16, 2020 (Accessed May 03, 2020).