India’s Affordable Defence Spending

Introduction

Defence expenditure is an important component of national security and every country allocates a significant portion of its resources for this purpose. However, given the scarcity of resources and the competing demands from other sectors, a nation’s ability to meet all its Defence requirements is not unlimited. Even the United States, the only military superpower, is unable to afford many of its major programmes, forcing it to scale down the number of items to be procured.1 The sheer size of the Defence budget and its impact on other sectors of the economy thus, more often raises the question as to how much a country can afford for its Defence.

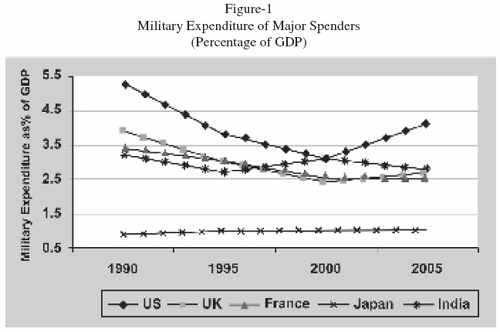

In the absence of any clear framework of evaluating affordability of Defence spending, many analysts tend to view the same from the perspective of a country’s share of Defence in gross domestic product (GDP) over a period of time, or by comparing these shares with those of other countries. This method of relative measurement, however, suffers from ambiguities as it does not take into account a country’s specific security concerns and the economic compulsions in its totality. In the global context, the affordability of military spending of some of the world’s major military spenders2 varies not only in degree but also from time to time (see Figure-1). While the variation in the degree of affordability indicates the changing security threats that are perceived differently by countries, the fluctuation in affordability over time points to the fact that what may be affordable at one point in time, may not be so at another time. Among the major powers, except for Japan,3 no other country has been able to sustain consistently high level of Defence spending (in percentage of GDP) over a length of time. The macro economy, which guides major spending heads of the government, could be a factor in controlling Defence spending over a period of time. In the US, the present level of military spending has contributed to fiscal distress,4 raising doubts whether such large-scale military spending is affordable or sustainable in the future.

In the light of the above, the article tries to examine affordability of India’s Defence spending. However, as illustrated above, there is no established or universally accepted framework of evaluating affordability as such, and the relative method of measurement does not take into account the economic aspects. The present article tries to approach the issue by taking into account different factors, but is restricted to an economic analysis. In particular, it examines Defence spending with respect to resource gap; estimates of the various Finance Commissions; fiscal responsibility of the government; the country’s national resources expressed in terms of the GDP; total resources available to the government; the priority of resource allocation; and financing of Defence expenditure.

Source: Figure derived from The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, at http://first.sipri.org/non_first/milex.php

Defence Projection and Allocation: The Resource Gap

India’s defence spending5 in current prices6 has increased substantially over the years, from nearly Rs. 1200 crore in 1970-71 to Rs. 1,05,600 crore in 2008-097 (this represents a five-and-a-half fold increase in constant prices, from nearly Rs. 13,418 crore to Rs 73,360 crore).8 In the last one decade, it has increased by an average of nearly 10 per cent per year from Rs. 47,070.63 crore in 1999-2000. A figure depicting India’s Defence spending since 1980-81 is appended at Annexure-I. Notwithstanding the growth in Defence spending, the Defence outlays do not necessarily match the demands of the Defence establishment. For instance, in the last five years, the unmet demand by the Services/Departments varies between some Rs. 5,880 crore and Rs. 26,150.7 crore, which is nearly 6-27 per cent of the total projected demands. The shortfall on the Revenue side ranges between 4 per cent and 13 per cent, and that on the Capital side varies from as low as 6.9 per cent to over 49 per cent (see Table-1).

The lesser percentage of ‘shortfalls’ in Revenue expenditure compared to that of Capital expenditure shows that while the former is more or less fixed, the latter is relatively flexible. At the same time, the ‘shortfalls’ both in absolute and percentage terms indicate that all the demands made by the Defence sector are not fully in conformity with the resources available with the government. However, over the past five years, the percentage ‘shortfalls’ are coming down, indicating that the government has found the wherewithal to afford and meet the increasing requirements projected by the Defence establishment over the past five years.

Finance Commission Estimates and Defence Expenditure

The Finance Commission of India, a statutory body under the Constitution, plays an important role in providing fiscal recommendations to the Government. The body is tasked, among others, to review the state of finances of the government, assess the requirements of the various sectors of the State and provide guidelines for distributing the State’s resources among the Centre and States. The recommendations of the Commission provide the basic foundation for restoring ‘budgetary balance, bringing macro-economic stability and equitable growth.’

The 11th Finance Commission9, after reviewing the broad requirements of the economy, acknowledged the need for steady growth in Defence Capital expenditure, and accepted the need for overall Defence budget to grow by 15 per cent per year during the Commission’s forecast period (2000-01 to 2004-05).10 Based on the projected ‘fiscal profile’ of the Central Government, the Commission assumed the Defence budget to reach the level of 3 per cent of the GDP by 2004-05, to meet the increased requirements of the Capital expenditure.11 However, at the end of the Commission’s forecast period, Defence spending increased by only 10 per cent per year, while its share in GDP was much lower than the Commission’s estimate of 3 per cent.12 As regards the growth of Revenue expenditure, the Commission also accepted a 10 per cent growth rate per year for the period from 2000-01 to 2004-05.13 Against this projected growth rate, the actual growth rate of Revenue expenditure during this period was 4.6 per cent. The corresponding growth figure for the Capital expenditure during this period was 21.4 per cent.14

Unlike the 11th Finance Commission, its successor, the 12th Finance Commission,15 allowed for a relatively moderate growth rate of 6.5 per cent per year for the Revenue expenditure for the five-year period from 2005-06 to 2009-10.16 In three years – from 2005-06 to 2007-08 – the annual growth rate on this account stood at 6.6 per cent,17 which was close to the forecast range provided by the Commission. However, unlike its predecessor, the Commission did not link the Capital expenditure directly with GDP,18 which grew by 14.5 per cent per year, in nominal prices, between 2005-06 and 2007-08.19 Compared to this, the Defence Capital expenditure during this period was increased by annual average of less than 8 per cent.20

If the recommendations of the past two Finance Commissions of India are taken into consideration, Defence spending has largely remained within the Commissions’ projected range and within the country’s macro-economic framework. The lesser percentage growth of Defence spending, when compared to its projected figures, suggests that the Defence expenditure has remained within the government’s desired objectives of budgetary balance, economic stability and equitable growth.

Fiscal Responsibility and Defence Expenditure

The ‘persistent fiscal problems’ of the country led the Government to pass the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, 2003. The Act required eliminating the revenue deficit and bringing it below 3 per cent of GDP by 2008-09. A Task Force, which was constituted to ensure this fiscal responsibility of the government, recommended a number of policy proposals pertaining to reforms in tax, and government expenditure.21 The ‘fiscal projections under the reforms scenario’, as estimated by the expert group, was expected to accelerate the GDP growth to 13.0 per cent per year, in nominal prices, by 2008-09.22 The higher growth of the economy along with the proposals under ‘reforms scenario’ was also expected to take Defence expenditure to a higher level and ‘stabilise’ it at 2.3 per cent of the GDP from 2006-07 to 2008-09.23 However, during this period, the growth of the economy though marginally outpaced the estimates of the Task Force, yet the percentage share of Defence in GDP fell short of 2.3 per cent of the GDP.24 If Defence were allowed to receive 2.3 per cent of the GDP, as projected by the Task Force, then between 2006-07 and 2008-09, it would have received nearly Rs. 95,000 crore, Rs. 1,08,000 crore, and Rs. 1,21,000 respectively. The Defence budgets for these three years are Rs. 89,000 crore, Rs. 96,000 crore, and Rs. 1,05,600 crores, respectively.25

The higher growth of GDP and the reduced share of Defence in it means some of the funds meant for Defence are, in fact, transferred to other sectors (especially towards interest payments and subsidies) so as to keep the FRBM targets under control. From the Defence point of view, the increased allocations that were expected to accrue to it due to the proposed reforms, have not fully materialised while its own spending remaining well within the estimated range of the country’s fiscal responsibilities, as outlined by the Task Force.

Gross Domestic Product and Defence Expenditure

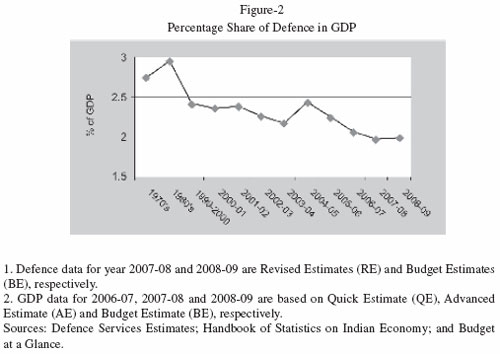

The percentage share of Defence in GDP is considered as a common measure of a country’s Defence expenditure and gives a fair idea about its affordability. On the basis of this, comparison is often made to see where a country stands vis-à-vis other countries, and also to arrive at a ‘norm’ by looking at a particular country’s own past trends.26 Going by this indicator, India’s current Defence affordability at around 2 per cent of GDP27 is less than its neighbours, especially Pakistan’s nearly 3.5 per cent and China’s over four per cent.28 Regarding the affordability ‘norm’ from the past trends, India’s Defence spending as a proportion of GDP is fluctuating and more specifically, on a declining path in the recent past (see Figure-2). Compared to the seventies and eighties, when the percentage share of Defence in GDP averaged 2.74 per cent and 2.95 per cent respectively, in the last one decade (1999-2000 to 2008-09), the average has come down to 2.18 per cent. Moreover, if the present growth rates of GDP and Defence spending continue, in the next one decade the share of the latter in the former will remain within 2 per cent of GDP. A matrix of projected GDP-Defence spending, at different growth rates, is appended at Annexure-II.

- Defence data for year 2007-08 and 2008-09 are Revised Estimates (RE) and Budget Estimates (BE), respectively.

- GDP data for 2006-07, 2007-08 and 2008-09 are based on Quick Estimate (QE), Advanced Estimate (AE) and Budget Estimate (BE), respectively.

Sources: Defence Services Estimates; Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy; and Budget at a Glance.

The declining share of Defence in GDP can be ascribed, among others, to the strong performance of Indian economy in the recent years. For instance, the Indian economy in the last 5 years (2003-04 to 2007-08) grew by an average of more than 14 per cent per year, in current prices, compared to less than 9 per cent per year during the previous five years. The strong performance of the GDP over the years means an enhancement of the country’s economic ability to afford more on various sectors including Defence. However, Defence, which earlier received a larger share of the national resources, is now receiving a declining share, and is consequently more affordable, in the relative terms.

Defence Expenditure and Central Government Expenditure

Unlike GDP, which gives the value of national resources generated in an economy in a given year, government expenditure gives the total resources available to the Government for allocation among different sectors. The pattern of allocations from the government expenditures suggests the priority attached on each allocation for each sector. Though this priority is best explained when Defence spending is expressed in terms of its share in Central Government expenditure, yet the analysis can further be extended to that of ‘General Government’29 expenditure (central and state together) to see the priority at the national level.

During the past one decade (1997-98 to 2006-07), total ‘General Government’ spending and total Central Government spending have increased significantly, by nearly 188 per cent and 168 per cent, respectively.30 On the other hand, the Defence spending has grown relatively lower at 142 per cent,31 suggesting that allocation for other sectors have increased at a faster pace. Over the last 5 years Defence spending as a percentage of total Central Government expenditure has been reduced from the peak of 15.9 per cent during 2005-06 to the low of 13.0 per cent during 2007-08 (RE) (see Table-2).32

The faster growth of both central government and total ‘General Government’ expenditure compared to Defence expenditure suggests that despite increased level of Defence spending, the government has been able to spend more on the non-Defence sectors. In relative terms and from the point of view of resource allocation, the decreasing share of Defence shows that the allocation for it is easily provided (affordable) over the years.

RE: Revised Estimate; BE: Budget Estimate.

Sources: Ministry of Finance, Budget at a Glance (relevant years) for Central Government Expenditure; and Government of India, Ministry of Defence, Defence Services Estimates (relevant years) for Defence Expenditures.

Major Heads of Government Expenditure and Defence Expenditure

The major heads of government expenditure can broadly be classified into Developmental expenditure and non-Developmental expenditure.33 During the 10-year period since 1997-98, the annual average growth of Developmental expenditure of both the ‘General Government’ and Central Government has been more than on the non-Developmental heads. Among the 10 largest heads34 of the general Government expenditure, Defence has recorded the lowest annual growth rate after Administrative Services.35 For the same major heads of the Central Government expenditure, Defence, though, has exceeded the overall growth of non-Developmental expenditure, yet compared to the major heads under Developmental expenditure, it has recorded the lowest growth rate after that of Power, and Irrigation & Flood Control (see Table-3 ).

The relatively faster growth of major heads of Developmental expenditure compared to that of Defence expenditure during the past decade shows that the growth of the latter has not hindered the government’s priority in terms of higher percentage allocation on major developmental goals. In other words, Defence, from the resource allocation point of view, has remained within the affordable limit, in the sense that it has not hampered the growth prospects of the economy.

Financing Defence Expenditure

Financing of government expenditure, including Defence expenditure, constitutes an important aspect of public finance, considering the role of various sources of government earnings and their impact on the economy. Over the last 10 years (1997-98 to 2006-07), the government’s total revenue earning has increased by nearly 216 per cent and, as a result, its share in the total government expenditure has increased from 68 per cent to nearly 75 per cent.36 The increase in revenue earning, which is mainly on account of increases in both tax and non-tax revenue, has helped the government in reducing the fiscal deficit and lessen the debt burden on the economy. While the tax and non-tax revenue have increased by 228 per cent and 172 per cent, the debt burden and fiscal deficits, measured by their percentage share in GDP, have decreased from 24 per cent to 16 per cent and from 4.81 per cent to 3.61 per cent, respectively.37 From the Defence point of view, the increase in the revenue earnings has lessened its percentage dependence on the latter, from 13.81 per cent to nearly 11 per cent. Besides, the surge in revenue earnings, which has reduced government’s dependence on the debt financing, has also reduced the share of the Defence debt38 on India’s “external outstanding debt” (see Table-4). In other words, in last 10 years, the financing of the Defence spending has become relatively easier on account of the government’s increasing earnings.

Conclusion

All the economic parameters examined in the article show that the allocations for Defence over the years have remained affordable, though, in some cases, in a relative sense. From the point of view of Defence requirements, the decreasing percentage shortfalls (between Defence projections and allocations to Defence) over the past five years indicate that the Government could increasingly afford the requirements projected by the Defence establishment. As far as the objectives of budgetary balance and fiscal stability are concerned, the Defence expenditure has largely remained within acceptable limits set by various Finance Commissions and the Task Force on FRBM and therefore, could not be blamed for the budgetary or fiscal imbalances, if any, in the economy. While the robust growth of the GDP and the consequent rise of Government revenues have significantly enhanced the country’s spending ability, the decreasing share of Defence in these resources indicates that the burden of Defence has reduced significantly. In terms of resource allocation and its priorities, the growth of Defence spending has not caused retardation in growth of spending in other sectors of the economy, especially in the developmental sectors.

Notes

- 1. US Government Accountability Office, Defense Acquisitions: Assessments of Selected Weapon Programs, Report to Congressional Committees, March 2008, at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d08467sp.pdf.

- 2. According to SIPRI, US, UK, France, Japan and India rank 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th and 10th in the list of countries with highest military expenditure in 2006. See SIPRI Yearbook 2007: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 270.

- 3. Japan’s military expenditure as percentage of GDP has remained constant at 0.9-1.0 per cent over the last 15 years, though a 1.0per cent of GDP resulted in $42 billion in current prices in 2006. See SIPRI Yearbook 2007: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security, Ibid, p. 313.

- 4. The continuous increase in military expenditure by the US since 2001 has led to increase in government debt and deficit financing. The Congressional Budget Office estimates total government debt over $5 trillion and federal budget deficit at 1.5 per cent of GDP in 2008. See Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2008 to 2018, January 2008, at http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/89xx/doc8917/01-23-2008_BudgetOutlook.pdf

- 5. Defence allocation in India, presented in the form of Defence Services Estimates, is broadly divided into two components, i.e., Revenue expenditure and Capital expenditure, and includes expenses of the Armed Forces, Defence Research and Development and Ordnance Factories. Revenue expenditure includes expenditure on Pay & Allowances, Revenue Stores (like Ordnance stores, supplies by Ordnance Factories, Rations, Petrol, Oil & Lubricants, Spares, etc), Revenue Works (maintenance of buildings, water and electricity charges, rents and taxes, etc) and other miscellaneous expenditures. The Capital expenditure includes expenditures on Land, Construction Works, Married Accommodation Projects and Capital Acquisitions (Aircraft & Aero Engines, Heavy and Medium Vehicles, Other Equipments, Naval Fleet, Naval Dockyards/Projects, etc).

- 6. Henceforth India’s defence spending/expenditure and its components are expressed in current prices unless stated otherwise.

- 7. Defence allocation for 2008-09 is Budget Estimate (BE). See Government of India, Defence Services Estimates, 1970-71 and 2008-09.

- 8. Defence spending in constant (1999-2000) prices is calculated by taking GDP deflator.

- 9. For the Commission’s report, see “Report of the Eleventh Finance Commission (for 2000-2005)”, June 2000.

- 10. Ibid, p. 41.

- 11. Ibid.

- 12. The Commission had assumed, among others, GDP to grow by 63 per cent from 2000-01 to 2004-05. The actual growth of GDP during this period is 49 per cent, representing a 22 per cent reduction in Commission’s estimates. The corresponding shortfall in Defence is 33 per cent.

- 13. Report of Eleventh Finance Commission, n. 9.

- 14. The growth rates of Revenue expenditure and Capital expenditure between 200-01 and 2004-05 are estimated on the basis of their respective figures as provided in Defence services Estimates (relevant years), n. 7.

- 15. For the Commission’s report, see “Report of the Twelfth Finance Commission (2005-10)”, November, 2004.

- 16. Ibid, p.100.

- 17. Revenue expenditure includes Actuals for 2005-06 and 2006-07, and Revised Estimate for 2007-08.

- 18. Rather, the growth of Capital expenditure was left to be taken care of by the Commission’s estimated growth of Central Government Capital expenditure as a percentage of forecast GDP. The Central Government Capital expenditure as a percentage of GDP was estimated by the Commission to grow at 7.6 per cent per year from 2005-06 to 2009-10. It is to be noted that the Defence Capital Budgets during the last two Commissions’ periods were increased by 21.4 per cent (11th Commission) and 9.9 per cent (10th Commission) per year, respectively. In such a case, it is difficult to understand why the Commission linked growth of Capital budget with a new benchmark.

- 19. For GDP figures of these years, see Government of India, Central Statistical Organisation, National Accounts, at http://mospi.nic.in/press_release_7feb08.pdf, p.5

- 20. Capital expenditure includes Actuals for 2005-06 and 2006-07 and Revised Estimate for 2007-08.

- 21. For the FRBM Act and Associated Rules, and the Task Force Report, see Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Report of the Task Force on Implementation of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act, 2003, July 2004.

- 22. Ibid, p.137.

- 23. Ibid. p. 160.

- 24. The GDP in current prices during the period from 2004-05 to 2008-09 grew at an annual average of 13.1 per cent. See National Accounts, n. 19. During the above period Defence accounted for 2.0 per cent of GDP.

- 25. See Defence Services Estimates (relevant years), n. 7.

- 26. Amiya Kumar Ghosh, India’s Defence Budget and Expenditure Management in a Wider Context, (New Delhi: Lancer Publishers, 1996), p.167.

- 27. India’s Defence allocation stands at 1.99 per cent of the expected GDP of the Fiscal Year 2008-09.

- 28. For Pakistan, see The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, at http://first.sipri.org/non_first/milex.php; for China, see CIA, The World Factbook, at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ch.html

- 29. General government includes both Central Government and State Governments together.

- 30. Estimated from Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, Economic Division, Indian Public Finance Statistics 2006-2007, June 2007.

- 31. Estimated from Defence Services Estimates (relevant years), n. 7.

- 32. Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Budget Division, Budget at a Glance 2007-08.

- 33. Developmental Expenditure is incurred on account of Railways, Post & Telecommunications, Social & Community Services, General Economic Services, Agriculture & Allied Services, Industry & Minerals, Power, Irrigation & Flood control, Transport & Communications, and Public Works, etc. Non-Developmental Expenditure is incurred on account of Defence Services, Border Roads, Interest Payments, Fiscal Services, Administrative Services, Organs of State, Pension & other Retirement Benefits, Relief on account of Natural Calamities, Technical & Economic Cooperation with other Countries, Compensation & Assignment to Local Bodies, Food Subsidy, Social Security & Welfare, etc.

- 34. The 10 largest heads of expenditure are calculated on the basis of 2006-07(BE) allocations on different heads, as provides in Indian Public Finance Statistics 2006-07, n. 28.

- 35. administrative Services include Police, External affairs and others.

- 36. Estimated from Indian Public Finance Statistics 2006-07, n. 30, p.3.

- 37. Ibid, p. 4 and 42; For India’s debt burden, see Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs, India’s External Debt: A Status Report, August 2007, pp. 39-41.

- 38. Defence debt here includes export credit for Defence purchase and Rupee denominated debt owed to Russia and payable through exports.

| Attachment |

|---|

Download Complete [PDF] Download Complete [PDF] |