Improving Global Food Security: The Impact of the Black Sea Grain Initiative

Summary: Global food security has been significantly impacted due to the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine. Rising food inflation and reduced availability of key commodities are some of the major concerns. To address these challenges, the Black Sea Grain Initiative was introduced, which has played a vital role in bridging the demand and supply gap and providing a degree of stability to global food prices. Given the significant consequences of non-cooperation, the continuation of this initiative is critical to safeguard the future of global food security.

The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine has triggered a polycrisis of global food, fuel and fertiliser insecurity. In February 2022, the cessation of exports from the region resulted in reduced availability and escalated costs, thereby posing a threat to the food security of several nations that are reliant on Russia and Ukraine for their food supplies.

To alleviate the effects of the conflict, the Black Sea Grain Initiative was introduced to regulate food supply. With Ukrainian grain reaching global markets and Russia’s recent decision to renew the deal for an additional 60 days, it necessitates an examination of the initiative’s impact on global food security. Amid debates over multilateralism, it is also imperative to recognise the benefits of cooperation in addressing non-traditional security challenges, as evidenced by this initiative.

What is the Initiative?

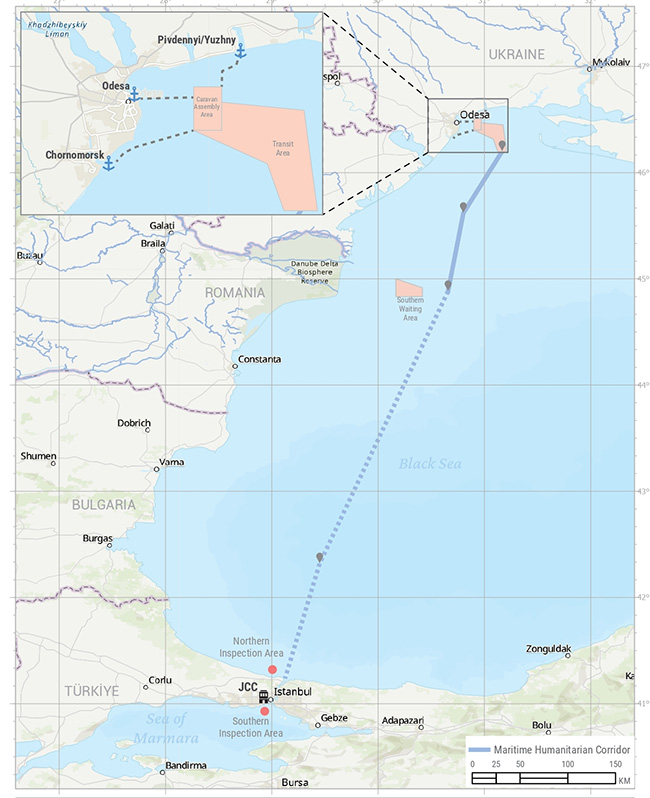

On 22 July 2022, the United Nations (UN) and the Republic of Türkiye brokered the deal between Russia and Ukraine to establish a safe humanitarian corridor for the transportation of grains and fertilisers from the ports of Chornomorsk, Odesa and Yuzhny/ Pivdennyi.1 The agreement aimed to address the growing global food insecurity concerns, rising prices and facilitate the unimpeded export of food, sunflower oil and fertilisers from the three ports.2 The deal was brokered after a series of parallel negotiations in April 2022 through the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) task forces dealing with Russian and Ukrainian representatives, respectively.3 Russia also entered into a separate Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the UN Secretariat to further facilitate trade and supply.4

Following the signing of the deal, a Joint Coordination Centre (JCC) was established in Istanbul to manage and monitor the export of food commodities. The JCC teams, comprising UN, Ukrainian, Turkish, and Russian officials, conduct inspections on ships arriving and departing from the ports to ensure compliance with regulations, including inspecting any unauthorised cargo and personnel on board. All merchant vessels are also subject to inspection during entry and exit from the Turkish Strait. The agreement prohibits attacks on civilian vessels and port facilities involved in the Initiative and mandates remote monitoring of vessel movements. Military ships, aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) are not permitted to approach the humanitarian corridor without JCC authorisation and consultation with all Parties.5

Source: “Resources”, Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre, United Nations.

Why is it relevant?

The relevance of the Black Sea Grain Initiative can be explained by two contextual factors. First, through an assessment of Russia and Ukraine’s pivotal role in the global food security nexus, making their cooperation vital in ensuring stable and secure food supplies. Second, an assessment of how the absence of this cooperation has significant repercussions, including disruptions in grain exports, reduced global availability, and endangered food security in several nations.

Their role in the food security nexus

Russia and Ukraine are considered “Global Breadbaskets”, as they are significant net exporters of agricultural commodities, including various cereals and oilseeds. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), in 2021, the two countries accounted for almost 30 per cent of global wheat exports and 78 per cent of global sunflower oil exports. In the same year, Russia was the top global wheat exporter, shipping 32.9 million tonnes of wheat and meslin, which is equivalent to 18 per cent of global shipments. Ukraine, meanwhile, was the sixth largest wheat exporter, shipping 20 million tonnes of wheat and meslin, accounting for 10 per cent of the global market share.6 Before the pandemic, they also supplied approximately 20 per cent of the global barley supply and 18 per cent of maize (corn) supply.7 Additionally, Russia is a major stakeholder in the global fertiliser market, being the top exporter of nitrogen (N) fertilisers and the second leading exporter of potassic (K) fertilisers in 2021. It was also the third leading exporter of phosphorus (P) fertilisers in the same year.8

The high levels of exports from Russia and Ukraine reflect a strong global dependence on these countries. Nearly 50 countries depend on them for at least 30 per cent of their wheat imports, with 26 countries sourcing over 50 per cent of their wheat imports from these two countries.9 This heavy reliance is particularly evident in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where countries such as Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Yemen, Tunisia, Jordan, and Morocco are heavily dependent on Russia and Ukraine for their food supply.10 For instance, Egypt imports approximately 70 per cent of its wheat from the Black Sea region. Prior to the conflict, the World Food Programme (WFP) also sourced half its wheat from Ukraine for its distribution programmes.11 The blockade of food exports from the region has had a direct impact on these countries, exacerbating their already fragile food security situation.

Their absence from global food markets

The abrupt exit of two key players from the global food market had a significant impact on food prices, as evidenced by the UNFAO’s food price index which reached an all-time high in March 2022. Averaged at 159.7, the index presented high prices for several commodities, including vegetable oils, dairy and cereals.12 Additionally, fertiliser prices experienced a sharp increase during this period. Global fertiliser prices are estimated to have risen by 199 per cent between May 2020 and the end of 2022,13 which was compounded by production issues and the imposition of trade sanctions on Russian fertilisers, as well as rising energy costs.

The absence of Russia and Ukraine from global food markets must also be contextualised in light of the reality that nearly 828 million people around the world face hunger and malnutrition.14 This is coupled with supply shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic, a declining global food stock inventory and an increasing disparity in food supply and demand. Several recipients of these commodities are Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries (LIFDCs) and multiple households have been pushed into a “food-poverty trap”, constraining their access to food. Declining food assistance and loss of crop and livestock due to climatic shocks have also worsened food availability in states with declared emergencies, including Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Haiti, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen.15 Inadequate access to food also carries the potential to further undermine political stability in these regions.

The current crisis, coupled with the challenges outlined, presents a significant threat to global food security. As the global food system has become more fragile and vulnerable, the Black Sea Grain Initiative has assuaged the demand–supply deficit to a certain extent and provided a degree of stability to global food prices.

Supply regulation through the Initiative

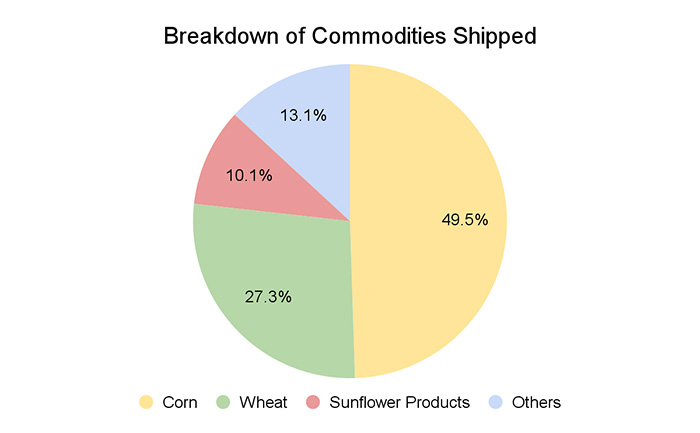

The Initiative has enhanced global food security by increasing the availability, affordability and accessibility of key food commodities. Since the commencement of the Initiative in August 2022, more than 1,600 vessel shipments have transported 24 million metric tonnes (MMT) of export commodities, including wheat, corn, barley, sunflower oil and soybeans.16 Corn and Wheat constitute 77 per cent of the total exports (Figure 1). The increased supply of food commodities through the Initiative has had a causal effect on global food prices, with the UNFAO’s Food Price Index declining for the 11th consecutive month in February 2023, dropping 18.7 per cent from its peak in March 2022.17 The Initiative has also played a critical role in re-invigorating port activity in the region, reducing transportation time and improving accessibility.18

Source: Created by Author; “Vessel Movements”, Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre, United Nations.

To fully comprehend the significance of the initiative in bridging supply gaps, it is imperative to analyse the export destinations of these food commodities. Wheat, one of the key dietary components for food security and nutrition, is being mainly supplied to low-income and lower-middle income countries. The initiative is also sending shipments of wheat to several Least Developed Countries, including 6,55,422 metric tonnes (MT) to Bangladesh, 2,05,618 MT to Yemen, and 1,30,869 MT to Afghanistan. This can potentially alleviate the looming hunger, malnutrition and food shortage crisis in these countries. Additionally, the initiative is effectively addressing food shortage concerns in Europe, where approximately 52.01 per cent of total exports have gone to Europe and Central Asia, with Spain, Türkiye, and Italy being the second, third and fourth largest beneficiaries, respectively. The MENA region has received 14.40 per cent of the total exports from the initiative.19 In addition to a regional overview, in developmental terms, more than 55 per cent of the total exports are being sent to developing countries. Supply resumption has also prevented food wastage as millions tonnes of grain stored in Ukrainian silos is reaching global markets.

China is the top recipient of exports from the Initiative. In 100 shipments, it has received 5.2 MMT of food commodities. Approximately 70 per cent of the shipments are of corn.20 Similarly, India has received 14 shipments of sunflower oil through the Initiative, amounting to 4,12,286 MT,21 which is a significant contribution given the challenges posed by erratic edible oil supply to India’s food security. In 2021, Ukraine was the largest supplier of sunflower oil to India.22 Presently, the country’s consumption of edible oil outstrips its domestic production, with imports accounting for nearly 60 per cent of demand. Sunflower oil makes up a notable 19 per cent of India’s edible oil imports, which have contributed to a high import bill of around Rs 1.57 lakh crore in the last fiscal year.23 The Black Sea Grain Initiative has, therefore, played a critical role in enabling this trade and bridging the supply gap.

Both India and China have also expressed their support for the Initiative. In a joint statement at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), India and Sweden supported humanitarian relief through the Initiative.24 China’s peace plan for Ukraine also emphasised the importance of an unobstructed grain supply and supported the UN’s efforts towards this goal.25 Furthermore, China released the ‘Cooperation Initiative on Global Food Security’ in July 2022, which called for unimpeded trade with Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, as well as enhanced cooperation with international organisations like the UN, WFP, and UNFAO, to ensure global food security.26

As displayed, the future of global food security hinges heavily on the consistent flow of commodities from Russia and Ukraine. It is therefore imperative to continue cooperation. However, the Initiative does not completely prevent certain issues arising from the arrangement. Firstly, there is still a significant gap in commodity flows from Ukraine. When comparing the wheat exports between the pre-conflict period of 2021 and the post-conflict period of 2022, there is a gap of 11.8 MMT. Similarly, there are gaps of 6.3 MMT and 4.2 MMT for corn and barley exports, respectively. Despite the Initiative’s efforts to regulate the supply, it has not been able to make up for the decline in trade that occurred during the initial months of the conflict.27 Secondly, the Initiative has not facilitated the supply of fertilisers, which is an inextricable link in maintaining food security. The soaring prices of fertilisers have exacerbated the crisis, and even though the agreement allows for the export of ammonia, shipments for the same are yet to commence. It is vital to remember that the MoU also facilitates Russian agricultural exports. In this regard, the UN had previously attempted to restart operations on a pipeline that transports ammonia from Russia’s Volga region to the port of Odessa, which had been shut down after the conflict.28 Despite Russia’s fervent demand, the resumption of the pipeline’s operations is still pending. Lastly, an interrelated issue is the ‘lag-effect’ of high prices on production and significant infrastructural damage, which has dented the supply chain structure. While the Black Sea Grain Initiative may offer immediate respite, as a rolling effect of the conflict, area under cultivation has shrunk and the estimates for 2023 production outputs have declined.29 The situation is compounded by increasingly prominent contextual factors, particularly the impact of climate shocks on production.

Future of the Deal

The deal was recently extended for 60 days on 19 March 2023. Prior to this, Russia temporarily withdrew from the agreement just before its initial renewal date in November, citing an alleged attack by Ukraine on its Black Sea fleet near Sevastopol. Similarly, Ukraine has accused Russian officials of intentionally slowing down vessel inspections and hindering the movement of grains.30 Over the course of the conflict, Russia has repeatedly threatened to withdraw from the deal and has demanded the removal of Western sanctions that indirectly impact its agricultural sector.31 It is worth noting that Ukraine’s agricultural sector plays a crucial role in driving its economy.

In a recent development, Russia has agreed to a 60-day extension of the deal. Ukraine has opposed Russia’s decision, arguing that the provisions of the agreement warrant a 120-day extension.32 Furthermore, Ukraine has requested a one-year extension of the deal and the inclusion of the port of Mykolaiv to increase its exports.33

In light of the uncertainty around the extension, as opposed to the prevailing notion, Russia may not abandon the deal so easily. The deal is Russia’s “gesture of goodwill” and a possible means to repair its damaged reputation.34 Additionally, it allows Russia to maintain ties with its allies in the developing world, particularly in the MENA region and China, many of which are facing unintended consequences of the conflict. Finally, the prerogative to continue or discontinue the deal continues to be a significant leverage for Russia, even if it is symbolic.

Conclusion

The Initiative demonstrates the importance of multilateral cooperation in addressing non-traditional security issues. Organisational mitigation of the UN and Türkiye’s third-country mediation has allowed to ease a dangerous food insecurity crisis. It has displayed the merits of a coordinated response to meet food shortage challenges. The successful collaboration has also softened the blow suffered by multilateralism in the wake of the conflict.

Two factors need to be ensured. First, it is of paramount importance to ensure the continuity of the deal. While it may not be able to address the deeper challenges of global hunger, it has been instrumental in alleviating immediate pressures, and in providing stability to countries teetering on the brink of collapse due to food unavailability. Secondly, as the conflict continues to escalate and uncertainty looms, it is critical to ensure that grains continue to flow to the Least Developed Countries and the developing world. Hoarding of grains must be prevented, which would only serve to exacerbate the current crisis.

The Initiative has effectively mitigated the negative impacts of the crisis and further underscores the need to continue collaboration. The costs of non-cooperation are high, making its continuation critical to secure the fate of global food security.

Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

- 1. “Initiative on the Safe Transportation of Grain and Foodstuffs from Ukrainian Ports”, United Nations, 22 July 2022.

- 2. Before the conflict, the three ports facilitated over 50 per cent of Ukraine’s maritime agricultural exports. David Laborde and Joseph Glauber, “Suspension of the Black Sea Grain Initiative: What has the deal achieved, and what happens now?”, Issue Brief, International Food Policy Research Institute, 31 October 2022.

- 3. “Black Sea Grain Initiative | Joint Coordination Centre | United Nations”, United Nations, Accessed 2 February 2022.

- 4. “Memorandum of Understanding between the Russian Federation and the Secretariat of the United Nations on Promoting Russian Food Products and Fertilisers to the World Markets”, United Nations, 22 July 2022.

- 5. “Initiative on the Safe Transportation of Grain and Foodstuffs from Ukrainian Ports”, United Nations, 22 July 2022.

- 6. “CL 170/6 – Impact of the Ukraine-Russia Conflict on Global Food Security and Related Matters under the Mandate of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 13–17 June 2022.

- 7. Hannah Ritchie, “How Could the War in Ukraine Impact Global Food Supplies? – Our World in Data”, Report, Our World in Data, 24 March 2022.

- 8. “Information Note – The Importance of Ukraine and the Russian Federation for Global Agricultural Markets and the Risks Associated”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 10 June 2022.

- 9. “The Impacts and Policy Implications of Russia’s Aggression against Ukraine on Agricultural Markets”, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 5 August 2022.

- 10. Caitlin Welsh, “The Impact of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine in the Middle East and North Africa”, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 18 May 2022.

- 11. Maytaal Angel, “WFP Ramps Up Food Aid to Ukraine amid Reports of Severe Shortages”, Report, Reuters, 5 March 2022.

- 12. “FAO Food Price Index | World Food Situation”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- 13. Douglas Broom, “This is How War in Europe is Disrupting Fertilizer Supplies and Threatening Global Food Security”, We Forum, 1 March 2023.

- 14. “The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022.

- 15. “2022 Global Report on Food Crises”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022;

“Hunger Hotspots FAO?WFP Early Warnings on Acute Food Insecurity October 2022 to January 2023 Outlook”, World Food Programme, 2022.

- 16. Data collected till 14 March 2023. “Black Sea Grain Initiative | Vessel Movements | United Nations”, United Nations.

- 17. “FAO Food Price Index Declines for the 11th Consecutive Month”, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 3 March 2023.

- 18. “A Trade Hope: The Role of the Black Sea Grain Initiative in bringing Ukrainian Grain to the World”, Report, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 20 October 2022.

- 19. “Black Sea Grain Initiative | Vessel Movements | United Nations”, United Nations.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Ibid.

- 22. “Production of Oil from Mustard Seeds Increased from 91 LMT to 101 LMT this year”, Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food & Public Distribution, Government of India, 9 September 2021.

- 23. “India’s Edible Oil Import Bill up 34% at Rs 1.57 lakh crore: Industry Body SEA”, The Economic Times, 14 November 2022.

- 24. “Joint Statement on Behalf of India and Sweden”, Permanent Mission of India to the UN, 6 December 2022.

- 25. “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 24 February 2023.

- 26. “Wang Yi Puts Forward China’s Cooperation Initiative on Global Food Security”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 24 February 2023.

- 27. “A Trade Hope: The Impact of the Black Sea Grain Initiative”, Report, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 9 March 2023.

- 28. Guy Faulconbridge and Michelle Nichols, “UN Trying to Get Russian Ammonia to World through Ukraine”, Report, Reuters, 14 September 2022.

- 29. Sampad Nandy et al., “Black Sea Agriculture Trade Tilts in Russia’s Favor after One Year of War in Ukraine”, Report, S&P Global Commodity Insights, 23 February 2023.

- 30. Pavel Polityuk, “Ukraine Calls On UN, Turkey to Prevent Russia from Obstructing Grain Deal”, Reuters, 15 February 2023.

- 31. Michelle Nichols, “Black Sea Grain Export Deal Extended, but Russia Wants More on Fertiliser Exports”, Reuters, 18 November 2022.

- 32. “Black Sea Grain Talks Continue as Russia Seeks 60-day Renewal”, Reuters, 14 March 2023.

- 33. “Can Ukraine’s Grain Corridor Ease the Global Food Crisis?”, The Indian Express, 16 February 2023.

- 34. “Russia Says It Shows “Goodwill” in Extending Grain Deal”, Reuters, 14 March 2023.